Artworks identified as Post-war and Contemporary are often clumped together when museums curate an exhibition or auction houses organise a sale, even though they are often considered by experts to belong to two fundamentally different movements. Their proximity comes from their common influences and the fact that they both emerged post World War II.

To understand the differences and similarities between the two, we have to travel back in time; to the birth of the Modern Art movement. In 1863, Édouard Manet unveiled Le déjeuner sur l’herbe at the Salon des Refusés in Paris. Like all artworks, it was influenced by those that came before it. However, it is considered by most to be the first to embody the key elements of a modern work of art. It was nonconformist, as evidenced by its rejection by the jurors of the official Paris Salon. It portrays an ordinary, everyday event as the subject rather than the splendour of the elite or divinity from the past. It veered towards abstraction to depict the real world rather than realism.

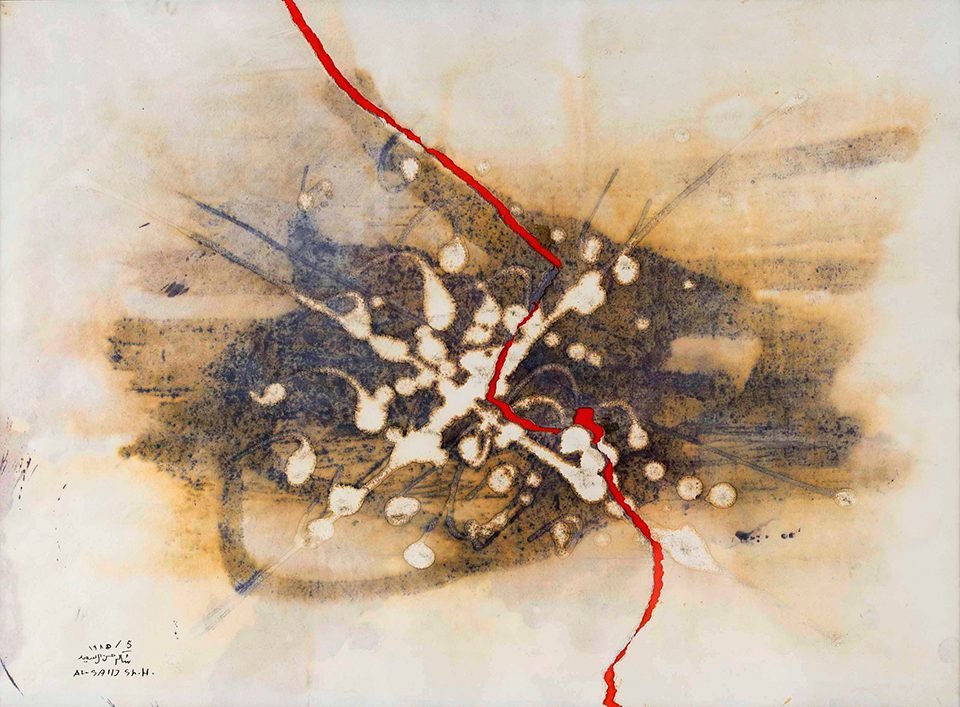

Women of Crafty Mysteries

Oil and ink on canvas

14 ½ x 15 ¾in.

Painted in 1985

Impressionism, Post-impressionism, Symbolism, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Abstract art, Expressionism, Cubism, Surrealism and Social Realism are just some of the numerous art movements that emerged between Manet’s painting and World War II. The immeasurable impact the war had on the socio-economic fabric of the world would inevitability affect the world of art.

Consensus is once again lacking on what exactly constitutes Post-war art. However, it is generally accepted that Post-war art comprises all the art movements that came into being after the end of the war and before the emergence of Contemporary art. This classification is over-simplistic, to say the least. The post-WWII world was bipolar, divided between the Capitalist West led by the USA and the Socialist East led by the USSR. This bipolarity was reflected in the art world as well.

The years before, and during, WWII, Europe witnessed an exodus of artists, scholars, dealers and collectors of art to New York. By the time the war ended, European capitals were in ruins, including Paris, the former epicentre of art. In unscathed New York meanwhile, the mixing of American and European aesthetics and money brought Abstract Expressionism to the fore. It became the first internationally dominant movement to emerge from the US art scene. Artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline and Mark Rothko, among many others, who worked, lived or exhibited in New York City became the vanguards of the movement.

In the Soviet Union, Art was under the overt direction of the Fine Arts Department, which officially has a preference for Socialist Realism – a style of idealised realistic art that glorified socialist values. Ironically, this style is related to the Social Realism movement that emerged in the Americas, and both trace their origins to the European Realism movement.

Artists in the two decades following WWII either complied with these two dominant movements or, like the non-aligned movement, chose a third path. Most of these alternatives became the fountainheads of the Contemporary art movement that we have today.

The Contemporary movement is in some ways more difficult to define than any that preceded it. The simplest definition is that it is the art of today. However, the art of today has been around since the 1950s. It is global with a seemingly endless combination of inspirations, materials, methods, concepts, and subjects. It distinguishes itself by the very lack of a manifesto – an organising framework or ideology.

The emergence of Pop Art in the 1950s, pioneered by artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein as a reaction to the dominant Post-War art forms, is generally accepted as one of the most important alternative movements, if not the most important, that led to the emergence of Contemporary art. As the name suggests, it portrayed subjects from popular culture such as advertising, comic books and everyday mass-produced objects.

Photorealism – a concurrent movement to Pop Art and popularised by artists like John Baeder and Chuck Close Richter – focused on creating hyperrealistic drawings and paintings, often using photographs. Conceptualism was pioneered by Robert Rauschenberg and Isidore Isou and carried forward by Jenny Holzer and Ai WeiWei. Here, the idea and the creative process behind an artwork becomes the subject.

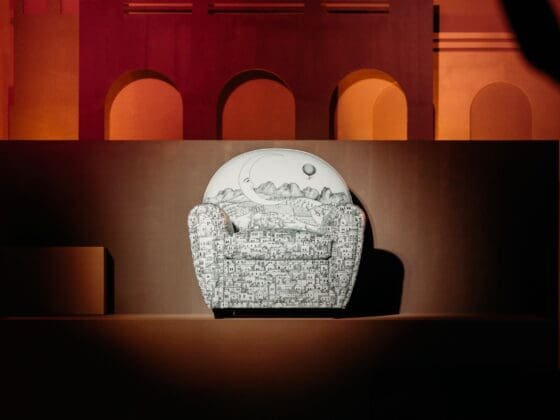

Untitled

Collage and watercolour on paper

14 x 18 7/8 in.

Painted in 1985

Installation Art and its variant Earth Art are both site-specific, often large and seek to create an immersive experience. Stree Art, or graffiti as some like to dismiss it, first claimed its own space in the 1980s with pioneers like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, and carried forward by the likes of Banksy and Shepard Fairey. Street Art has challenged art orthodoxy like no other, and in doing so, also embodies the nonconformist ethos of the Contemporary movement like no other.

The Modern Art movement emerged to challenge the establishment’s definition of art. Post-WWII, the descendants of the founding movements became the establishment. The Contemporary movement emerged to challenge the new establishment. It has been doing it for over 70 years. Some of the more recent Contemporary artists have expanded the medium of expression to include such disparate forms of art as embroidery, origami, tattoos and even AI-driven visual art. By this evidence, Contemporary art is still resisting any attempts to define it and is likely to do so in the foreseeable future as well.

Christie’s has led the international market for Post-War and Contemporary Art over the last decade. The auction house has Post-War & Contemporary Art auctions scheduled on the 25th and 26th June in New York, 29th and 30th June in Paris, followed by an Aristocratic Private Collection auction in London on July 23rd.