A closer look at the life of the legend Leonardo Da Vinci and his renowned painting, the Salvator Mundi, that was sold for a record-breaking $400 million on the fifteenth of November 2017.

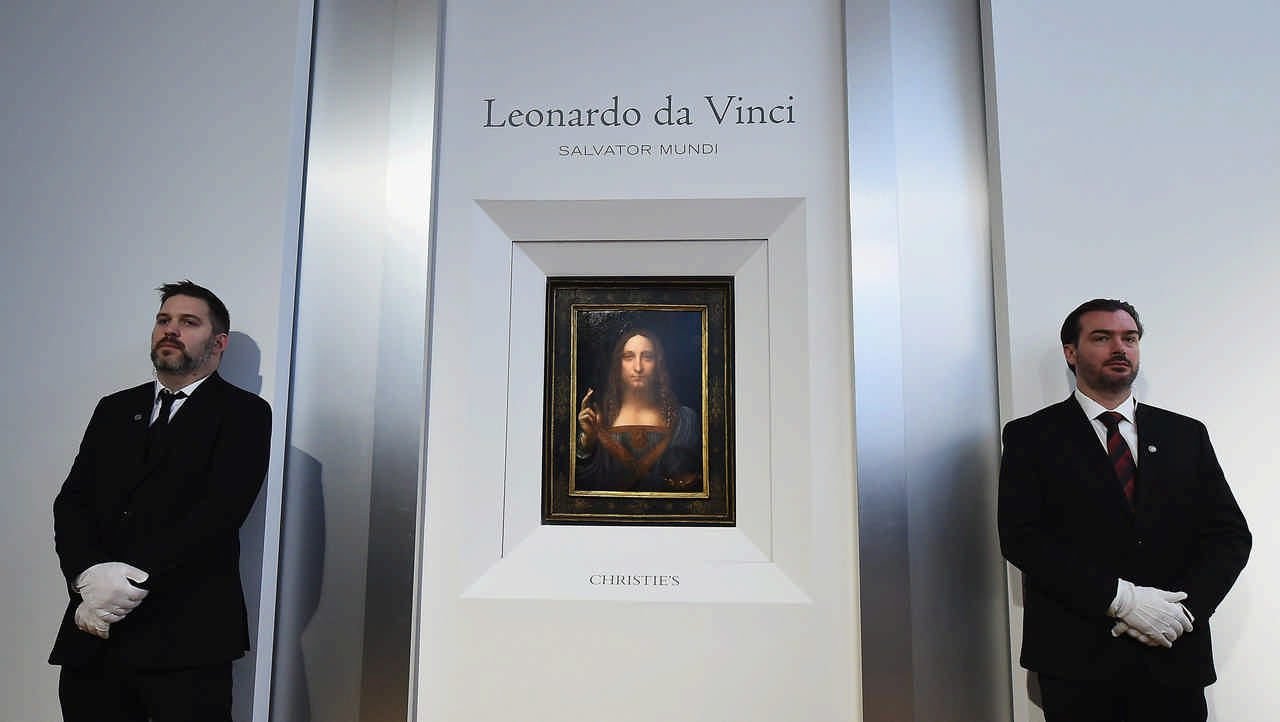

‘Salvator Mundi’ is a Latin phrase, and it means ‘savior of the world’. It is part of Christian iconography and depicts Jesus giving a benediction (blessing) with his raised right hand with three of the fingers unfolded symbolising the Trinity. In the left hand, he is depicted holding a divine object such as a bible, as in some earlier and eastern depictions, or an orb symbolising the created Universe.

Leonardo da Vinci was not the first to paint a ‘Salvator Mundi,’ and he was certainly not the last. So what makes his so highly valued? The answer has much to do with the artist himself.

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci was considered one of the greatest, if not the greatest example of a Renaissance polymath; or the archetypal Renaissance-man if you will. His insatiable quest for knowledge led him into a broad spectrum of inquiry such as mathematics, engineering, anatomy, botany, geology, cartography, astronomy, history, literature, and music. He is also considered a pioneer in the fields of palaeontology, ichnology, and architecture. But his raison d’être was unquestionably his painting.

“His father’s most telling contribution to his son’s life was that at the age of fifteen, he got him an apprenticeship under the famed Florentine master sculptor, painter, and goldsmith Andrea del Verrocchio”

He was born out of wedlock in 1452, to a notary attorney and a peasant woman in a village near Vinci, then on the outskirts of Florence in Tuscany. When he was about five, his mother married, and he was sent to live on his father’s family estate. His uncle, who possessed an appreciation for nature, helped raise Leonardo, and who had the greatest influence on him in those formative years. His father provided him with basic education which consisted of reading, writing, and maths. His father’s most telling contribution to his son’s life was that at the age of fifteen, he got him an apprenticeship under the famed Florentine master sculptor, painter, and goldsmith Andrea del Verrocchio. Leonardo spent the next decade learning and fine-tuning his skills as a painter and sculptor until he became a master in his own right in 1478. By this time he had already produced two masterpieces; ‘The Annunciation’ and ‘Ginevra de’ Benci.’

About four years later, Leonardo left for Milan to work for the ruling Sforza as a painter, sculptor, architect, and designer of events. His stay in Milan lasted for about seventeen years and were some of his most productive. It gave us ‘The Last Supper,’ one of Leonardo’s most admired and studied works. It also gave us ‘The Virgin of the Rocks,’ ‘Portrait of a Musician,’ and the Portraits of ‘Cecilia Gallerani’ and ‘La Belle Ferroniere.’

With the fall of the Milan Duchy in 1499, he returned to Florence and stayed for about seven years. This period gave us ‘Saint John the Baptist’, ‘The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne’ and of course the ‘Mona Lisa’; his other greatly admired and studied work. In this period, he also began work on the ‘Salvator Mundi.’

In 1506, Leonardo returned to Milan for the second time and stayed for about seven years, then to have to leave again. This time he went to Rome. Then in 1516, the king of France, Francis I offered him the title of ‘Premier Painter, Engineer and Architect to the King.’ Although he now had the time to work in leisure, he did not produce any artistic work of significance. He breathed his last in 1519 at the age of 67.

“Of the paintings he did complete, and those that have survived are true masterpieces of his age”

Leonardo da Vinci did not produce many completed works in his lifetime, to begin with, primarily because of his obsession with perfection, which meant he took a long time to complete a project. Of the paintings he did complete, and those that have survived are true masterpieces of his age. Here are some of his landmark works.

‘The Annunciation’ (1472) on display at the Uffizi, Florence, depicts the announcement by the angel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary that she would conceive and become the mother of Jesus. It has all the trademarks that would later become synonymous with da Vinci; the dreamy background, the detailing on the vegetation, and the attention to the drapery. The objects which seem to have gotten exceptional attention were the wings of Gabriel. A hint of his later fascination with flight maybe?

The portrait of ‘Ginevra de Benci’ (1474-78) on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. It is a portrait that added greatly to his reputation. It is exceptional in the way da Vinci uses light and shade to give depth to facial features. Then there is the detailing of the eyes and lips to create a haunting expression. Many see this as the prelude to the ‘Mona Lisa.’

The two versions of ‘The Virgin of the Rocks.’ The older one (1483-85) is displayed at the Louvre in Paris, and the second (1491-99 and 1506-08) at the National Gallery, London. The first is considered more of a da Vinci because it was all his brushwork, and his original and unconventional rendering of Christian convention. But it was considered too heretical by the clerical sponsors of the painting. So he had to make a second one, which was a compromise to please them.

The ‘Portrait of a Musician’ (1486-87) is admired for the detailing and visual depth given to the young male subject’s brownish eyes and his curly locks.

Two portraits, one of ‘Cecilia Gallerani’ (1489-90) and one of ‘La Belle Ferroniere’ (1493-94) are both exceptional in the way facial detailing is used to convey the subjects’ personality. Gallerani comes off as a lively free-spirit who is barely contained by the frame. Ferroniere, on the other hand, is intense and mysterious.

The Last Supper (1490-98) is a giant fresco-like painting on a wall at the Santa Maria delle Grazie monastery in Milan. Probably the most studied and copied of all da Vinci’s works, but also the most damaged. It was highly innovative for its day and gives an almost cinematic feel when viewed; as though one has paused a moment in a complex dramatic scene.

The ‘Mona Lisa.’ The most recognisable and enigmatic of da Vinci’s paintings. Volumes have been written on it, but no word can capture the subtle beauty of that smile, nor can they unlock the secrets well-guarded by those eyes.

Then, of course, we have the ‘Salvator Mundi.’ Like the subject it depicts, the story of the painting has also gone through a similar sequence of ups and downs. An exalted beginning, a disappearance into the wilderness, a reappearance and a final resurrection once again to exalted heights.

The story begins with Louis XII of France commissioning da Vinci to paint the image of Jesus giving the benediction. By 1625 it was in the possession of Henrietta Maria, and it came with her to England when she married Charles I of England. It was on display in her private chambers in Greenwich. When Charles I was executed in 1649 at the end of the English Civil War, all of the royal possessions came under the English Commonwealth, including the ‘Salvator Mundi.’

In 1650, Wenceslaus Hollar a renowned printmaker publishes what he calls ‘Leonardus da Vinci pinxit’ and claims it is a print of what later came to be known as da Vinci’s ‘Salvator Mundi.’ It was also listed in the Royal inventory and valued at £30. It was sold to John Stone in 1651, a Mason, to settle his debts. When the monarchy was restored in 1660, the painting was returned to the new king Charles II and was included in the inventory of his possessions at the Palace of Whitehall. His successor James II of England inherited it and was then passed on to a succession of royal relatives until Sir Charles Herbert Sheffield auctioned the painting in 1763.

The painting then disappears from the record for over a hundred and thirty years. It re-emerged in 1900 and was purchased by a collector named Francis Cook for an unknown amount. The painting by now had been damaged by poor restoration attempts and as a result was attributed to Bernardino Luini, a student of da Vinci. A black and white photograph from this period, now well publicised, show the extent of the damage done to the painting. Then in 1958, Francis Cook’s great-grandson auctioned it off for £45. By now the painting was attributed to another of da Vinci’s pupils – Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio. This attribution remained until 2011.

In 2005, the painting was again put on the auction block. This time in New Orleans. It was purchased by a consortium of art dealers that included Robert Simon, a specialist in Old Masters. This event marks the turning point in the history of the painting. It was the beginning of its resurrection. The members of the consortium came to believe that there was a possibility of it being the lost ‘Salvator Mundi’ of da Vinci. They handed the painting to Dianne Dwyer Modestini, Senior Research Fellow, and Conservator of the Kress Program in Paintings Conservation at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, for a long and painstaking restoration, followed by an authentication process.

Like most high-value works of art, particularly a da Vinci, the ‘Salvator Mundi’ was bound to have its share of controversy and entranced differences of opinions. To begin with, several reports have claimed that the ‘Salvator Mundi’ was the last Leonardo in private hands. The Duke of Buccleuch owns da Vinci’s ‘Madonna of the Yarnwinder.’

With regards to the ‘Salvator Mundi’ itself, there are two main areas of contention. The first is with regards to how much damage has been done and how much of da Vinci still remains in the painting. The Christie’s website states that according to Modestini, “the original walnut panel on which Leonardo, who was known for his use of experimental material, executed ‘Salvator Mundi’ contained a knot which had split early in its history. However, she concludes that important parts of the painting are remarkably well-preserved and close to their original state. These include both of Christ’s hands, the exquisitely rendered curls of his hair, the orb, and much of his drapery… With regards to the face… the discrete losses, the flesh tones of the face retain their entire layer structure, including the final scumbles and glazes. These passages have not suffered from abrasion; if they had, I wouldn’t have been able to reconstruct the losses.”

The second point of contention is with regards to a claim by a rival painting to be the real ‘Salvator Mundi.’ Once again, according to Christie’s website, in 2008 “the painting is taken to The National Gallery, London, where it is studied in direct comparison with ‘The Virgin of the Rocks’, Leonardo’s painting of approximately the same date. David Allan Brown (Curator of Italian Painting, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), Maria Teresa Fiorio (Raccolta Vinciana, Milan), Luke Syson, the Curator of Italian Paintings at The National Gallery, Martin Kemp (University of Oxford), Pietro C. Marani (Professor of Art History at the Politecnico di Milano), and Carmen Bambach of the Metropolitan Museum of Art are among those invited to study the two paintings together.

“the Salvator Mundi was painted by Leonardo da Vinci, and that it is the single original painting from which the many copies and student versions depend”

Later, the authenticity of the piece as an autograph work by Leonardo was confirmed by Vincent Delieuvin at the Louvre, Paris.” Then in 2010 “the painting is again examined in New York by several of the above, as well as by David Ekserdjian (University of Leicester) and a broad consensus is reached that the Salvator Mundi was painted by Leonardo da Vinci, and that it is the single original painting from which the many copies and student versions depend.”

Then in 2011, the resurrection of the ‘Salvator Mundi’ was complete. It is unveiled at The National Gallery in London as a painting by the Master Leonardo da Vinci. However, not all are convinced, and detractors remain and will remain.

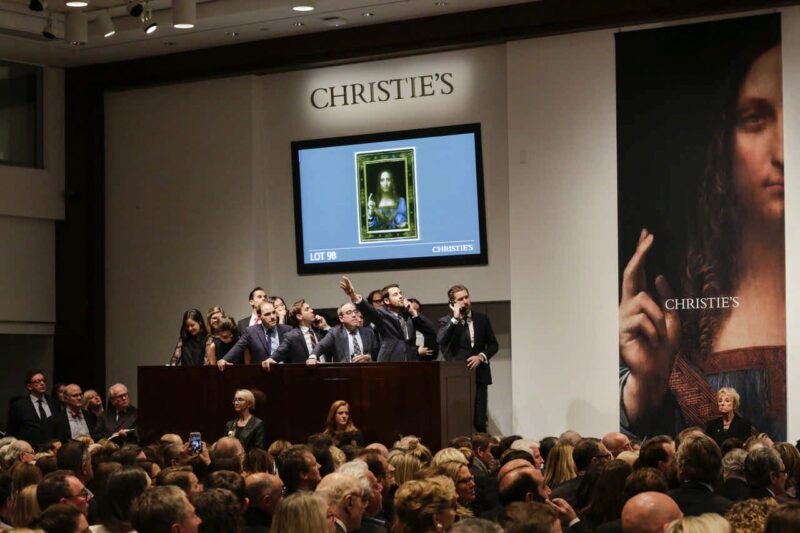

The record-breaking sale then added another layer of controversy. Prior to the auction, most experts had put a valuation for the painting at, or just over, the $100 million mark. The final price bid before the hammer came down, left everyone astonished. Once senses were regained, opinions started flying thick and fast. The museums lamented how they are being priced out of the market. The political left used it as proof of the disproportionate distribution of wealth. Some simply lamented or mocked that the buyer has bid too much. Other simply speculated who the mystery buyer was.

The New York Times in a Dec 8, 2017, article (online) stated that it “reviewed documents related to the sale that identified the previously anonymous winner of the auction as Prince Bader bin Abdullah bin Mohammed bin Farhan al-Saud, a descendant of an outer branch of the royal family. He has no publicly known history as a major art collector and no publicly known source of great wealth. But he is a contemporary, long-time friend and a close associate of the crown prince, and prominent Saudi royals have been known to make high-profile purchases through straw buyers”. The Saudi Embassy said in a statement that Prince Bander “acted as an agent for the ministry of culture of Abu Dhabi”. The Times was not convinced with this explanation because “American officials familiar with intelligence reports on the matter, and Arabs familiar with the details of the sale, both reiterated on Friday (Dec. 8) that the crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, was the true buyer at the time of the auction”.

Whatever the truth may be, the fact of the matter is that the painting is coming to the Louvre Abu Dhabi. Conceived by architect Jean Nouvel, it is a stunning piece of architecture finished in white with water features. Its signature piece being a ‘floating’ web-patterned dome which allows sunlight to pass through. Located on the Saadiyat Island’s Cultural District, it has a total floor space of about 24,000 square meters, of which about 8,000 square meters are for gallantries.

According to its website, it aims to be “a universal museum in the Arab world” which means “focusing on what unites us: the stories of human creativity that transcend individual cultures or civilisations, times or places. This ethos guides the museum in everything it does: from its foundation as collaboration between two cultures to the dazzling architecture that combines French design with Arabic heritage”.

By becoming a home to the newly resurrected ‘Salvator Mundi’, the museum has taken a giant stride in its walk towards fulfilling its stated objective. The ‘Salvator Mundi’ once again bears its Master’s name, has patronage from royalty and will soon have pride of a place in an architectural jewel in the desert. A resurrection indeed.