Alhambra, the name evokes images of the resplendent architectural masterpiece in Cordoba that seems frozen in time. For Van Cleef & Arpels, Alhambra is the name of a timeless classic with a humble beginning, but one that has grown to become an icon of the maison in 2018. 2018 also marked the 50th anniversary of this “lucky” charm, and to celebrate the occasion, Van Cleef & Arpels organised an event in Marrakesh where it launched four new necklace and bracelet sets.

Though it was born in revolutionary times, Alhambra came into existence not as a revolutionary but as an important evolutionary step in the story of Van Cleef & Arpels. The big step came in 1954, with the opening of La Boutique in Place Vendome. This made it possible for the maison to successfully transition from being a manufacturer of haute joaillerie for the very elite, into one that could also cater to a new type of woman; one who was financially independent, intellectually liberated and insistent on making her own decisions.

This transition by Van Cleef & Arpels was contemporaneous to the transition that was taking place in the world of haute couture where pioneers such as Pierre Cardin and Yves Saint Laurent had introduced their prêt-à-porter lines. Their safari suits, kaftans, tunics and daywear dresses were a perfect complement to Alhambra’s aesthetic. Nicolas Bos, the Van Cleef & Arpels’s president and chief executive told the New York Times, “It was a period where many things changed culturally. Jewellery and fashion were opening up to a wider clientele with modern lifestyles — that of the active woman who was buying for herself, with pieces worn for pleasure on a daily basis.”

Attending the 50th-anniversary event, among others, were artists who had collaborated with Van Cleef & Arpels to contribute to the landmark event. Photographer Valérie Belin has captured her vision of luck and the Alhambra long necklace on two occasions for the Maison. The Franco-Turkish duo of Burcu and Geoffrey directed an animated film that was illustrated by Julie Joseph that is part of Van Cleef & Arpels’s ongoing 360 global campaign for the Alhambra collection.

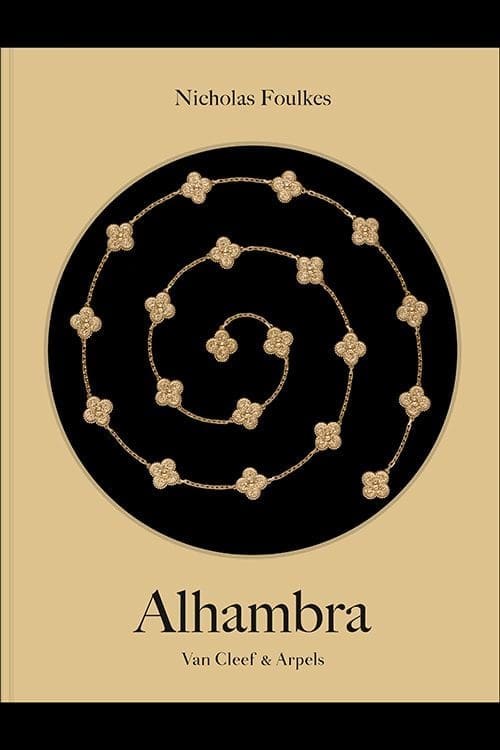

The maison also used the occasion to launch a new book by British author Nick Foulkes which traces Alhambra’s journey set against the changing socio-economic conditions of the last 50 years. The book is extensively researched and chronicles how a piece of jewellery became a symbol of a revolutionary era. It also features documents from the archives of Van Cleef & Arpels as well as an extensive collection of photographers. Foulkes is a believer in luck and believes that luck has been on Alhambra’s side for the past 50 years.

Luck, as a concept has been integral to Van Cleef & Arpels from its earliest days. “Luck is part of the tradition of what Van Cleef & Arpels does. In the First World War, they had touch wood rings, they had elephant hair rings that were supposed to be lucky,” Nick Foulkes told Signé during a recent visit to Dubai. Jacques Arpels, who managed the maison through the troubled times of World War II, once said: “To be lucky, you have to believe in luck.” He collected four-leaf clovers from his country house garden on the outskirts of Paris, pressed them, and fondly gave them to his staff along with an inspiring poem.

This sort of design concept, that is “sort of part geometric part natural world,” Nick Foulkes observed, “then comes together in something like the Alhambra. It is completely geometric, so you can abstract it. It’s also sufficiently looking like a four-leaf clover to be actually called the four-leaf clover.” Although the exact provenance of Alhambra motif remains a mystery, it is generally believed that it is based on a four-leaf, clover-shaped gold medallion created by Jacques Arpels as a fusion between the traditional Moorish quatrefoil and the lucky four-leaf clover.

Van Cleef and Arpels’ Alhambra was born in 1968 as an opera-length necklace of creased-gold featuring four-leaf clover motifs with beaded edges but did not feature hard stones. It was added to Van Cleef & Arpel’s more affordable, easy-to-wear Paris La Boutique range of day jewels. Subsequent versions featured hard stones such as lapis lazuli, malachite, coral, onyx, tiger’s eye and turquoise. By the late 70s, mother of pearl, carnelian, rock crystal and blue agate were added. It became a favourite of style icons such as Princess Grace of Monaco, Romy Schneider and Françoise Hardy.

Nick Foulkes notes that by the 1980s, due to the economic slump and changing fashion trends in Europe, the epicentre of demand for the Alhambra had moved to Japan as “there was something about it that appealed to the Japanese.” As elaborated in the following interview with Foulkes, the Japanese then played a crucial role in the resurgence of Alhambra in the west. These resurfaces led to the Alhambra watch making its debut in 1998 with its distinctive four-leaf curves. Materials such as Sèvres porcelain, chalcedony, and letterwood were introduced. In 2001, customers were given the option of a new sleeker version with smooth edges called Pure Alhambra, alongside the rough-edged original which was rebranded Vintage Alhambra.

For the 50th anniversary, Van Cleef & Arpels has created four limited-edition designs. One is a new interpretation of the Vintage Alhambra in grey mother-of-pearl, the most popular material for Alhambra designs, along with diamonds in pink gold. The suite includes a necklace, bracelet, earrings and a ring. Another version features onyx and diamonds in white gold. A more exclusive suite, one that will be produced in very limited numbers, consists of two versions of the Vintage Alhambra necklace and bracelets in yellow gold. One version features lapis lazuli and diamonds, while the other features rock crystal with 20 four-leaf clover motifs like the original.

The Alhambra collection now comprises 226 pieces including necklaces, pendants, bracelets, cufflinks, earrings, and watches, which makes up about half of Van Cleef & Arpels’ total jewellery offering.

Going by this remarkable timeless icon’s ability to evolve and adapt while retaining its simple yet distinctive silhouette, like all true design classics tend to do, one would have to conclude that Van Cleef & Arpels’s Alhambra will adorn women for many years to come.

To get a greater insight into Alhambra’s remarkable yet largely obscure history, there is no better place to start than Nick Foulkes’ insightful book on the design icon titled “Van Cleef & Arpels: Alhambra.” Foulkes, a graduate of Hertford College Oxford, is the author of around 25 books on arts and history. He also contributes to a wide range of newspapers and magazines around the world including FT’s How To Spend It Magazine, Vanity Fair, and Country Life and luxury among others.

On his recent visit to Dubai, he shared some of his experiences while writing the book, his opinions on the Alhambra collection, and the reasons for its continued popularity.

How did your collaboration with Van Cleef & Arpels come about?

I had done a book on Automata for Van Cleef & Arpels which was more predictable in that it is the kind of thing I do. I like to write history books and books on the arts and material culture. The Alhambra book was slightly different because although I had written a couple of books on Jewellers and Jewellery, there are people who are better experts in the history of Jewellery. But Nicolas Bos, who’s a lovely man, wanted me to do it and I said I’d give it a go.

They approached me because the anniversary was coming up and it transpired that nobody really knew very much about the origins of Alhambra in-house. It just sort of existed. Then it really took off about 10 or 12 years ago and then everybody started paying attention to it. No one was really sure why it was called Alhambra or where it came from. They knew it was created in 1968. They knew that a few of the famous people had worn it in the 70s and that was about it.

How did you approach the writing of Alhambra, was it different from the other books you’ve done?

I set out to write the kind of book that I would like to read about Alhambra. One that would answer for me the questions I have about it. I never know exactly what I’m going to write before I sit down to write it which I think is the correct way to do it. I don’t predetermine. It’s like seeing what information I can get and then using that information to tell a story.

When I went through Van Cleef’s archives, I saw the Alhambra motif appearing here and there. Everybody was taking it for granted that the Alhambra motif had been in a kind of aesthetic deep-freeze but actually what I found was that it had adapted itself to the times.

It was a great experience for me to look through the archives of Van Cleef & Arpels. I took so many megabytes of photography because every page you turn, there’s something wonderful. Whether it’s the crown jewels of the Shah of Persia, or a design for an astrological belt buckle, or an iconic tissue box holder. There are all sorts of weird and wonderful things these books reveal.

How long did the research take and how did you structure it?

We needed 18 months. I was doing other things as well of course. It was a real jigsaw puzzle because you have to look in the archives, then you look in all sorts of newspaper archives, then you speak to old employees, you go to their headquarters to look at what’s being done now, and you gradually begin to build up this picture. I had to also read quite a lot about the events in Paris in May in 1968 because you should know what was going on politically, the level of affluence, and so on, to get a better understanding.

What do you attribute to Alhambra’s longevity?

I think there are a number of things. One factor is luck. Everybody needs luck, and thankfully Van Cleef & Arpels had the luck in Paris to be run by Pierre Arpels who was far-sighted enough to open the boutique in Paris. Then he went to Japan when nobody else was going to Japan, and they started selling the Alhambra in Japan. Though it may have seemed out of step in the 1980s in the west, there was something about it that appealed to the Japanese. So it was a lucky move that made Van Cleef & Arpels the favoured brand of one of the most powerful economies in the world at that time.

Then a Japanese photographer sparked a sort of a revival. He did these hyper-saturated images of picnics that were very elaborate. Then the Alhambra seemed to be everywhere. There were a lot of knock-offs as well which obviously irritated Van Cleef & Arpels and in a way it was flattering too.

The Alhambra is very wearable, and it is very versatile. It’s got a visual language that speaks to you. The Alhambra was intended to be worn every day rather than worn on occasions.

Do you think the Alhambra customers see it as a lucky charm?

Undoubtedly because, before it was known as Alhambra, it was just a piece of jewellery that had a bunch of names that were workshop names essentially. In the advertising, it was sometimes referred to as Clover to wear with jeans or a ball gown. It was called Alhambra officially, but it wasn’t always called that in the brochures and advertising. So yes, I think people do believe it is lucky.

How do you define an icon and how do you see Alhambra evolving in the next 50 years and so?

An icon is something that draws strength from multiple reproductions rather than getting vandalised by it. It’s like some of the Andy Warhol images; they gain their power and their commercial value from being reproduced, and they become recognisable.

“Another thing that defines an icon in the world of jewellery, watches and personal ornaments is the adaptability or the number of times that a design can be tweaked, and the variation that you can get out of it while it still remains essentially recognisable. The number of different variations of the Alhambra I think is well over 250.”- Nick Foulkes

Is there anything you’d like to add?

The Alhambra is like an iceberg. The one-tenth above is that which you can see with your eyes, and the nine-tenths below is this book where you have all the background, the people who made it, where it came from, how it fitted in with Van Cleef’s other creations and so on. Only Van Cleef & Arpels could have made the Alhambra at that time, and it was at a time when they were also doing the crown jewels for the Shah of Persia.