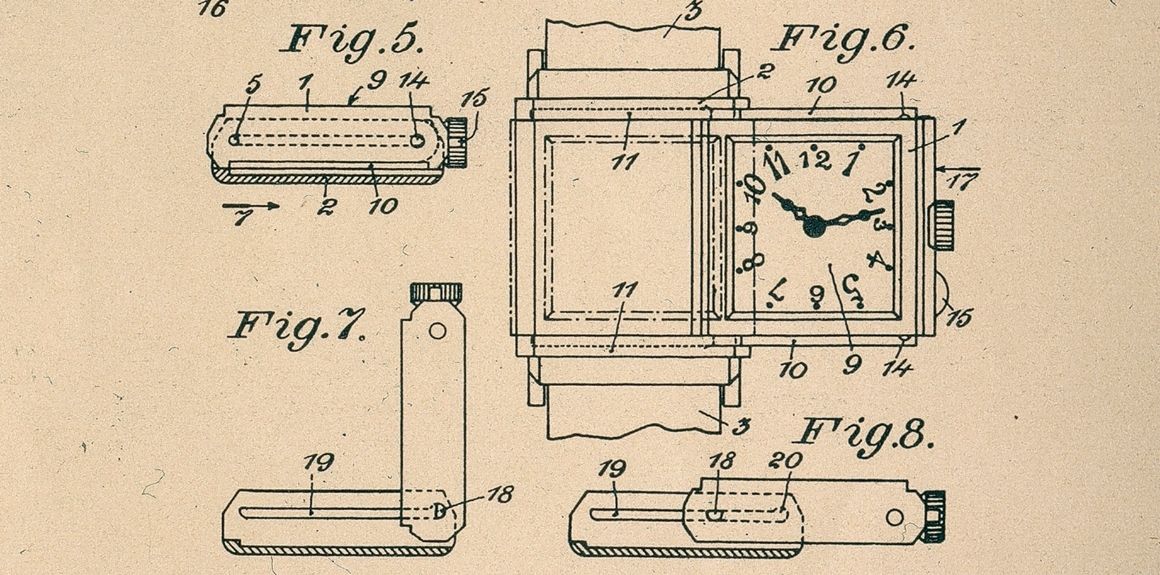

On March 4 1931, the Paris patent office received an application from French industrial designer, René-Alfred Chavot to register “a watch capable of sliding in its support and being completely turned over.” César de Trey, a successful entrepreneur and watch dealer, had commissioned Chavot to design the case, and called it Reverso. He had penned an agreement with LeCoultre & Cie to manufacture it. Today, 90 years later, the Reverso is not only being manufactured but has grown into a signature collection at Jaeger-LeCoultre.

César de Trey, the story goes, did a lot of business in India selling watches. He sensed a business opportunity when the polo-playing British officers of the Raj requested him to find a way to protect the glass and dial of their wristwatches during matches. This led de Trey to the idea of a case that could be flipped over.

Nine months after Chavot’s patent application being filed, the first batch of Reverso wristwatches was on sale. They were an immediate success, and tastemakers from all walks of life adopted the Reverso. It had several core design elements that not only distinguished it from its peers but were crucial to its success.

The proportions of the original rectangular case – the ratio of its length to width – was based on the golden mean. As a result, the case sat snugly on the wearer’s wrists. The ingenious engineering of the flip mechanism produced the tactile pleasure of the case as it glided along its carrier, followed by the satisfying click as it locked into place.

In a world where silvered dials prevailed, the original Reverso models featured a black dial with contrasting indexes, offering exceptional legibility. Its horizontal gadroons emphasise the case’s rectilinear geometry, while the triangular lugs appear to be a seamless extension of the case sides.

As with every successful model, aesthetic variations soon began to appear, starting with made-to-order coloured dials – bright red, chocolate brown, burgundy, blue or others – at a time when coloured dials were rare in watchmaking. Different case metals, including gold, and re-sized models for women were offered to be worn on a cordonnet bracelet or transformed into pendants or handbag clips.

While its blank metal flip side began as a purely functional piece to protect the dial, it became an ideal surface for personalisation with monograms, emblems or personal messages using lacquer, engraving or enamel. The owner could keep this decoration as a personal, hidden treasure or flip the case over so that its back becomes the front. This feature makes the Reverso unique in the world of luxury watches to this day.

Jaeger-LeCoultre museum houses several examples of decorated Reverso examples from the 1930s. There is one with the emblem of the British Racing Drivers Club. A piece with the Eton College coat of arms. A 1935 Reverso commemorates the record-setting flight from Mexico City to New York by the aviator Amelia Earhart.

In India, the Maharajah of Karputala commissioned 50 Reverso watches, with a miniature-painted portrait of his wife reproduced on the caseback in enamel. Although these pieces are all believed lost, Jaeger-LeCoultre has a similar Reverso in its collection, dating from 1936, with a portrait of another Indian beauty, thought to be Kanchan Prabha Devi, Maharani of Tripura State.

Following World War II, there was a rejection of ornamentation in all areas of design, which meant interest in the Reverso and its elaborated decorations waned. When the first quartz wristwatches entered the market in 1969 – triggering the Quartz Crisis – the Reverso seemed destined to the footnotes of history had it not been for Giorgio Corvo, Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Italian distributor. He bought the last remaining 200 Reverso cases, had them fitted with mechanical movements, and sold every piece within a month. Thus, in 1975, the Reverso was officially reborn.

Jaeger-LeCoultre decided to bring the production of the Reverso case in-house and, in 1981, assigned one of its engineers, Daniel Wild, to redesign it to modern technical standards. The new case was unveiled in 1985. Given Reverso’s status as a design classic, the aesthetic changes were almost imperceptible. However, It comprised 55 parts, compared to the 23 of the original. Waterproof and dust-proof, the new case had redesigned flip-over mechanism, lug attachments and carrier. It also became the first case to be machined at Jaeger-LeCoultre using the then-new CNC technology.

The revival of mechanical watchmaking in the 1990s also sparked a renewed interest in dying artistic crafts such as enamelling, miniature painting and guillochage. In 1996, Jaeger-LeCoultre released its first set of timepieces decorated with grand feu enamel in modern times. Appropriately, the maison chose a set of four Reverso watches, each bearing a perfectly reproduced miniature of a work by the Art Nouveau master Alphonse Mucha.

Enamelling became a signature of the Reverso collection and, to this day, Jaeger-LeCoultre remains one of the very few Manufactures to have its own in-house enamelling atelier. Engravers, gem-setters and guillochage masters joined the Manufacture’s enamellers – all of them eventually brought together in one vast studio in 2016, with the establishment of the Atelier des Métiers Rares. This atelier has produced high Jewellery models featuring invisibly set baguette diamonds over the entire case; a cordonnet bracelet reinterpreted entirely in diamonds; case backs transformed into glittering expanses of snow-set diamonds.

For the first six decades, the Reverso was a time-only watch that offered exceptional decorative possibilities. However, in the 1990s, with the revival of mechanical watchmaking, Jaeger-LeCoultre began to realise its potential as a platform for high complications, despite the added challenge that rectangular movements require an entirely different architecture.

Thus, the Calibre 824 was developed in 1991, especially for the Reverso Soixantième. It indicated the date, by a central hand, along with the power reserve. This was followed in 1993 by the Reverso Tourbillon – the Manufacture’s first wristwatch tourbillon. Then came the Reverso Répétition Minutes in 1994. Jaeger-LeCoultre had, for the first time, miniaturised a minute repeater for a wristwatch. Its Calibre 943 became the world’s first rectangular minute repeater movement.

In 1996, the Reverso Chronographe Rétrograde had an intricate display on the reverse side that solved the problem of how to arrange the chronograph counters within a rectangular frame. This was followed two years later by the Reverso Géographique and, coinciding with the Millennium, the Reverso Quantième Perpétuel. Naturally, these pink-gold limited-edition pieces are highly sought-after by collectors.

The Calibre 879, developed for the Reverso Septantième, released in 2002, provided an 8-day power reserve – very rare at the time. Five years later, the Reverso Grande Complication à Triptyque introduced Calibre 175: a single movement incorporating 18 different functions, including civil time, sidereal time and a perpetual calendar, displayed on three dials – the third dial being set into the carrier plate of the watch.

The Reverso has also housed Jaeger-LeCoultre’s unique bi-axial flying tourbillon, first in the Reverso Gyrotourbillon of 2008 and again in the 2016 Reverso Tribute Gyrotourbillon. And in 2012, Jaeger-LeCoultre introduced the Reverso Répétition Minutes à Rideau, in which the chiming mechanism is activated by the movement of a pair of theatre-style curtains as they reveal and conceal the dial.

César de Trey, 90 years ago, would never have imagined that his idea would become a design icon of the 20th-century, let alone spawn a whole collection of exceptional mechanical pieces of art; appreciated as much for their art as their mechanics. Even when those at Jaeger-LeCoultre thought the Reverso was finally done, it proved them wrong and rose like a phoenix. With its distinctive Art Deco design, Reverso has dared to be itself without compromise, while reinventing itself through nine decades of social change, shifting tastes and advancing technology.