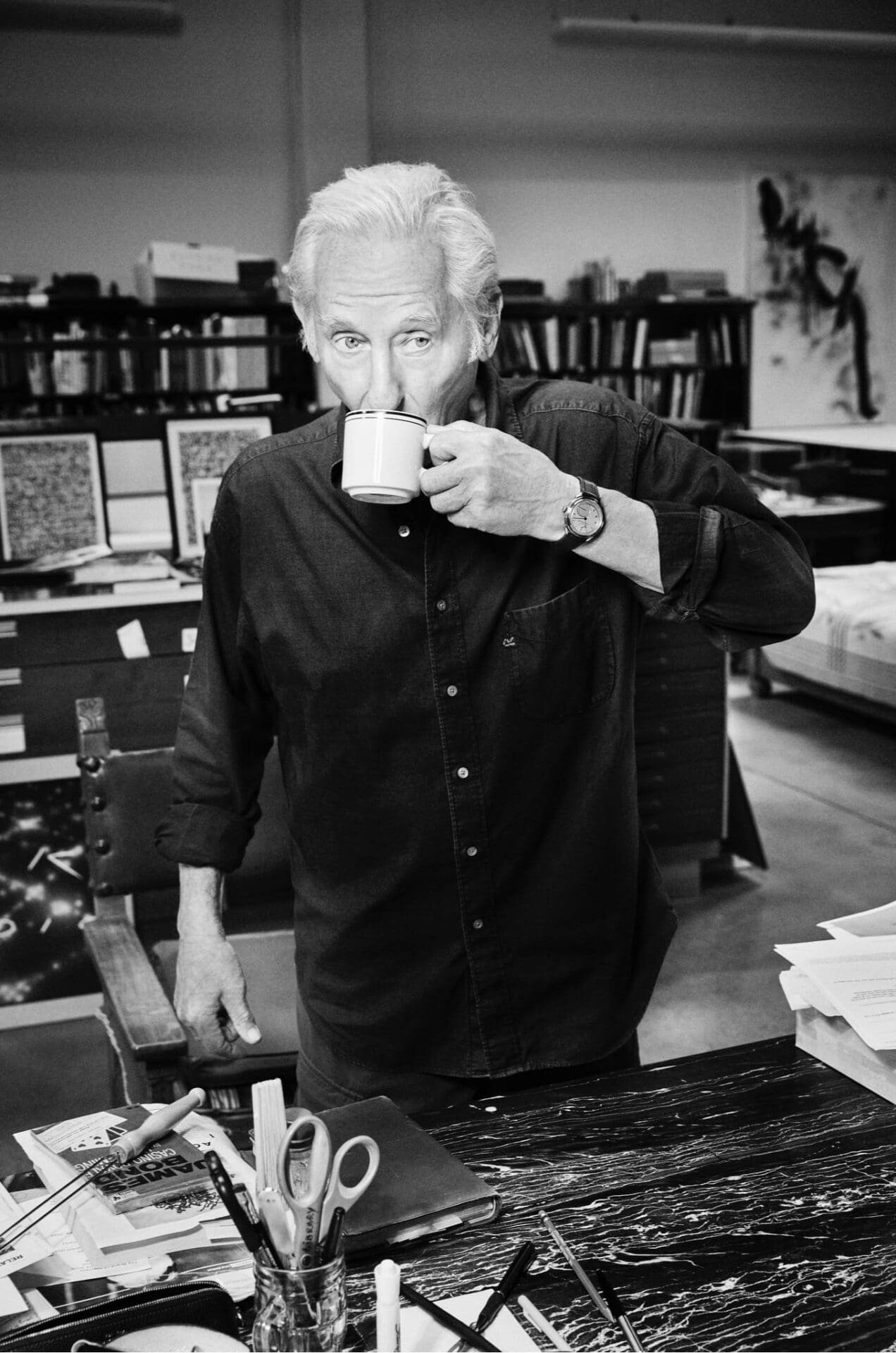

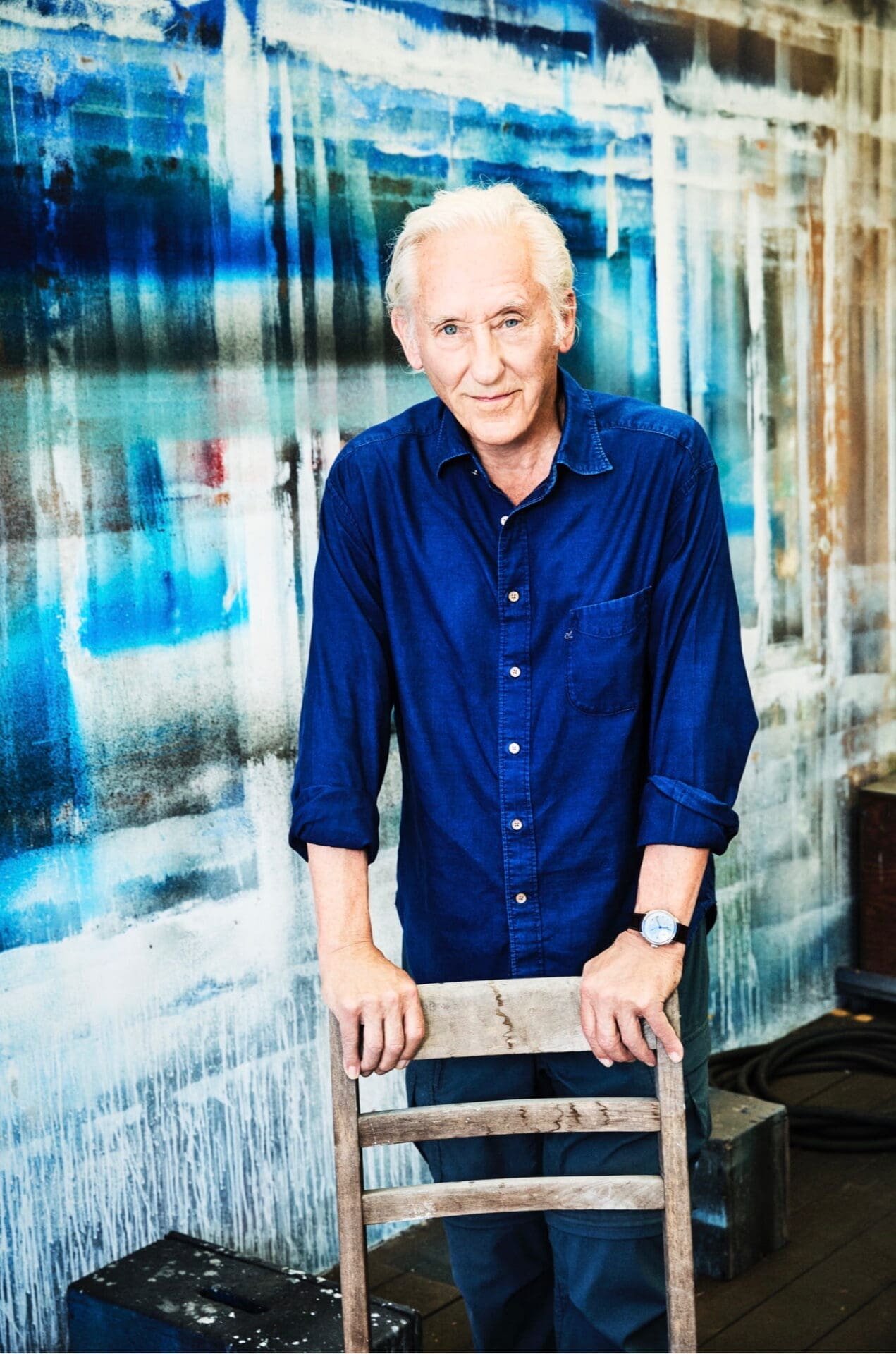

For the January chapter of Time Well Spent, Ed Ruscha is invited into focus, not as a monument of modern art but as an endlessly curious observer of the everyday. Inside his Los Angeles studio, decades of work unfold as a quiet but radical act: the elevation of the ordinary into something iconic. In Ruscha’s world, time is not rushed or dramatized; it is patiently spent noticing, collecting, and transforming the small details most people pass by.

Raised in Oklahoma City and permanently captivated by California after a childhood visit, Ruscha arrived in Los Angeles with an infatuation that shaped an entire career. Educated at the Chouinard Art Institute, he resisted the dominant pull of Abstract Expressionism, instead gravitating toward clarity, intention, and recognisable forms. Words, streets, signage, gas stations, and buildings became his raw material, forming a visual language that was cool, deliberate, and deeply rooted in lived experience.

From the 1960s onward, Ruscha expanded his practice across painting, photography, printmaking, and unconventional materials. Onomatopoeic words sit boldly across canvases, photographs document the evolving character of the Sunset Strip, and works constructed from substances like chocolate, gunpowder, grass stains, or caviar blur the line between concept and material poetry. Across every medium, play and experimentation remain constants, guided by an instinctive belief that curiosity itself is a discipline.

Time, for Ruscha, has never been about spectacle. Instead, it is about repetition, patience, and returning to ideas from new angles. A phrase, a logo, or a roadside structure can be revisited again and again, gaining meaning through restraint and persistence. This long-view approach has allowed his work to mirror American culture over decades, quietly documenting shifts in language, desire, and identity without ever becoming didactic.

The philosophy of Time Well Spent aligns naturally with Ruscha’s approach. It celebrates lives defined not by urgency, but by devotion to craft, thought, and observation. In this context, his practice becomes less about productivity and more about presence—about allowing ideas to emerge slowly and authentically through attention to the world as it is.